Recently, I took in (as one says) two thought-provoking photography exhibitions at Berlin’s C/O Art gallery. The first, entitled ‘Eyes Wide Open!’, mapped out 100 years of photography taken with the Leica camera. The exhibition defied chronology; save the small date which was displayed seemingly unimportantly below each photograph, the attention was turned towards the medium itself. It was clearly significant how the medium had advanced over the century, yet, given that all of these momentous historical events had been captured through the same 35mm lens, the effect was to unite the 100 years of photography; taking each image back to the original, personal moment which inspired it. Inside each black and white image was the snapshot of human experience, which had been petrified and made timeless.

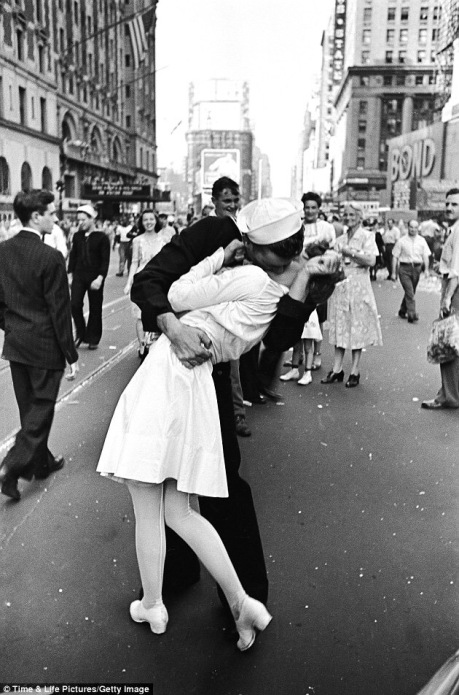

Among the images which have become iconic of great historical moments were The Man Jumping the Puddle by Cartier-Bresson, The Kissing Couple in Times Square by Alfred Eisenstaedt and the Vietnamese fleeing from Napalm by Nick Út.

The second exhibition was ‘Compatriots 1977 – 1987: Two Germanys’ which depicted selected photographs by Rudi Meisel of life either side of the former East-West German border. What struck me about this exhibition was the lack of stark differences between the Eastern and Western scenes. I caught myself regularly having to check the description card below each image to try to contextualise which side of the wall it had been taken in. The photographs illustrated the prosaic, everyday life of average people who were going about similar, unremarkable lives, regardless of what political system they were under. On both sides of the wall boys were playing football in empty car parks, elderly women were lined up at bus stops and chubby babies were being pushed along in prams. The only overt distinction between the otherwise arbitrary assemblage of photographs which could have been taken from the same family album, was the occasional glimpse of a western brand name on someone’s bag.

This made me reflect that an image only becomes significant when it is placed in a particular context, and retrospectively imbued with external cultural and political associations. Our collective memory of an event or period in history is dependent upon the images which are most dominant in the public domain and become our reference point for that time. Indeed, pictures can lie; a particular image can become sensationalised and can cause us to adopt a distorted impression of the past. I remember my A-level art teacher once telling me that the Monalisa was of little artistic skill or value, but rather it cost so much due to ‘a lot of hype’.

That is not to diminish the two exhibitions I saw today. The style (small sized, black and white images on a sparse background) stripped the images back to the singular moment in time that they represented. In that moment the person that image is disarmed, unaffected and true.

Looking out of the first floor window of the C/O towards the bridge of Zoologischer Garten train station — a busy, central location in the former West of Berlin — I looked upon the life outside as though I were a photographer waiting to catch a significant moment. The buzz from beneath the window was the sound of lives intersecting and people interacting; individuals woven into a network of others. So many noteworthy encounters or events could have been happening around me in that very moment.

I wondered what the most iconic image would be of this year, this day, this moment in Berlin. Would it be a young mother on a bicycle with a trailer attached to the front carrying her red-cheeked and beaming litter of three, whose voices warble with glee as she rides over the cobbles of Prenzlauer Berg? Would it be the Turkish wedding band singing and dancing outside Curry 36, summoning the bride from her apartment block in Mehringdamm? Would it be the crazed, wailing shuffle of a troubled drug addict staring at the camera with wild, glazed-over eyes clutching onto a carton labelled ‘Sangrhia’?